Ph: 06 280 0938

Individualism to Collectivism (how the h*ll do we do that!?)

It was once all about me…

As a kid growing up, I can remember it was my feats as an individual that were the ones that got me the most kudos. While I was also credited when helping others, it never had the same status as individual endeavour.

As I matured, the feats of individuals succeeding for themselves was highlighted and focussed on time and time again. The likes of Gandhi, Mother Teresa and later Nelson Mandela were often overshadowed by the individual bastions of industry and sport.

Being self-made was the Kiwi pinnacle of success.

When embarking on my own professional pathway, my measure was of course how well ‘I’ was doing, and that mostly meant what was my level of financial gain. There was no sense of what impact I was having on the environment, or my own wellbeing, or social impact…in any of the strategic thinking or planning around me. Just, ‘How much money can I accumulate while doing the business?’

Looking to nature for guidance

In 2022, I am intrigued by how we might go about unravelling the thinking that has been the scourge of the world the past few hundred years – or more? The question, ‘How do we create a legacy that helps others?’ is so much more rewarding.

I’ve read many business books about performance, and that hasn’t really helped. I’ve read sports books that are all about competition and winning, and that hasn’t helped.

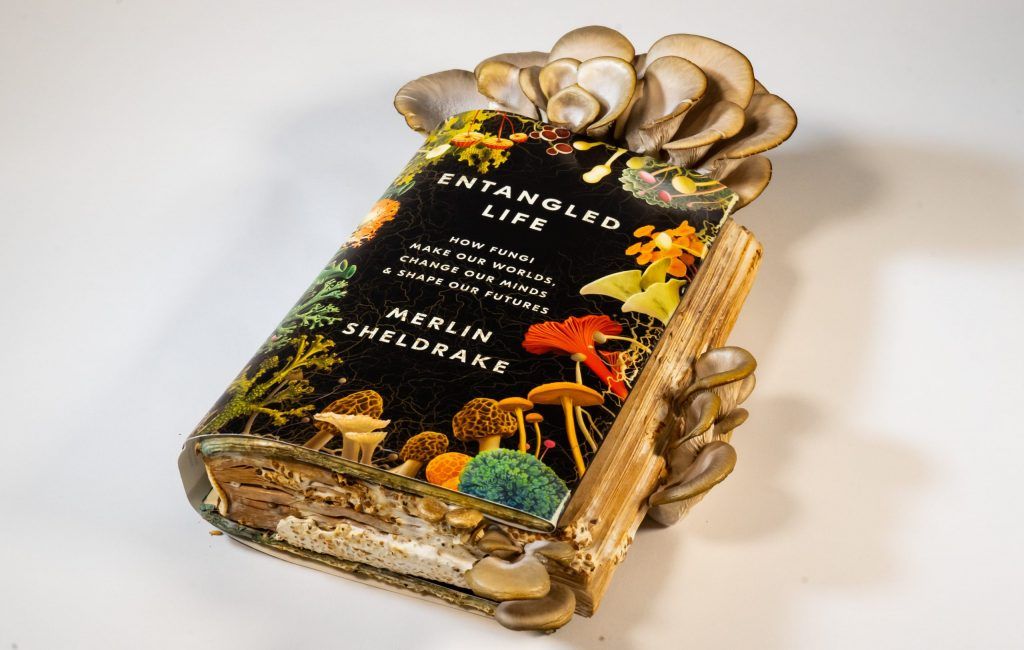

So what a delight to read over the long summer break books about a) fungi (Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake) and b) trees (The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben). Both gave me inspiration and a glimpse of what is possible…what we can learn, adopt, and copy to create a better future.

As a non-biologist, I thought I’d share with you here what I have learned so far and the fascinating similarities I see between these natural ecosystems and our own people-ecosystem that is Collective Intelligence.

Fungi and mycelia – transforming our understanding of our planet

Fungi are not that well understood as they have only been properly researched in the past 50 or so years. There is still very little known about them and their complex role in our world.

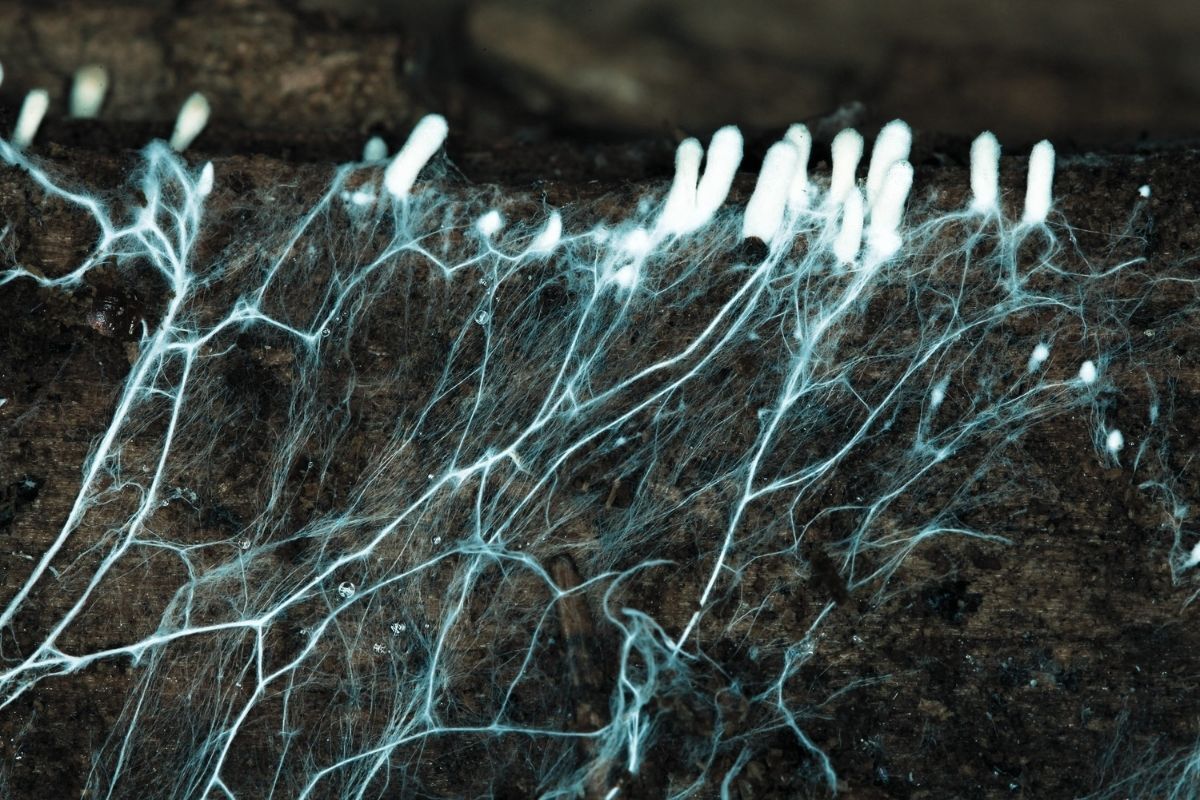

The fungi we see on the ground (mushrooms and the like) have this stuff underground that looks like a cobweb – called a mycelium. Mycelia make up the biggest living biomass class in the world – by a long way. They can live for thousands of years if they are not sprayed or ploughed up. As a living organism, a mycelium actively senses and responds to its surroundings (often in unpredictable ways) as it searchs for more food. When faced with many choices, a mycelium will branch off and take several routes at once.

A mycelium is a type of ecological connective tissue that ingests and transports nutrients, and water, not just for the fungi, but also surrounding trees and grasses. Without it, the soil is buggered, as it holds soils together and stores water. Mycelia are possibly the most important living things on this planet.

A mycelium network has no head, or central brain and is basically a decentralised organism. Mycelia can regenerate themselves and coordination takes place both everywhere, and nowhere, all at once. Left alone, they could be immortal.

They have incredible sensing powers – attracted to things that appeal and away from things that don’t. Mycelia are intelligent. They can choose. They form a dynamic and responsive network. They can’t run away from danger so instead they remodel themselves as a flexible network.

Then there is this stuff called mycorrhizal fungi – critical members of the plant microbiome that form a symbiosis with the roots of most plants. Basically, their job is to seek out other living organisms to form symbiotic relationships with. They look for partners who can do what they can’t do on their own. For example, mycorrhizal fungi can mine phosphorus in the soils and share it with plants, which can then grow quicker. Wicked eh!

In return, mycorrhizal fungi can partner with plants to photosynthesize for them and provide the fungi with sugars. They are like ecosystem engineers and are altruistic.

Some other very cool things about fungi that I took away from my reading:

- We know that ecosystems are complex and that there is no single fungal solution that will work in all sites and all conditions.

- Mycorrhizal fungi spend more time-sharing resources (via mycelium networks) with other plants, than competing with them.

- Interestingly – fungi spend as much time in decomposition as composition. About a fifth of all plant and animal species rely on dead wood to survive.

- And radically – fungi will send out a toxic substance into the soil to kill pest insects, releasing nitrogen for trees if they are in dire straits. Again – wicked eh!

And…this guy, Paul Stamets, is like the godfather of fungi:

Trees – interconnected forest ecosystems

An undisturbed healthy forest is happier and more productive than any human-managed forest. They like sorting themselves out.

Trees will pump nutrients towards each other to help each other via their underground mycelium networks. Nutrient exchange and helping your neighbours in times of need is the norm. Forests are a form of superorganism laced together with interconnections – not just a random cluster of individual trees. Once connected, they actually do not have a choice but to exchange.

Why would trees do this? By themselves they cannot establish a consistent local climate. Every tree is valuable and worth keeping around for as long as possible. Even when they die they are important. By themselves they are not a forest.

By themselves they can grow too fast, allocating so much energy into growth that they don’t put energy into protecting themselves. When that happens, they are vulnerable to being attacked by insects and other forms of ‘nasty’ fungi.

A tree is only as strong as the forest that surrounds it, and so intuitively they do not hesitate to help each other out. Trees need to be open-to-partner with many thousands of fungi, as these will literally grow into their soft root hairs.

A diverse range of tree species provides security for ancient forests as well as promoting a diversity of fungi – as they all rely on creating stable conditions. They support other species under the ground, through their roots, so that they are not as vulnerable to one species collapsing.

Young seedling trees in a natural forest will quickly become tied up within a complex, interwoven, and stable parent tree network from the get go. As they get older, they grow faster and are less fragile as they age, due to this interconnectedness.

Their network needs to be a flexible network. While they are ruthless in wanting to survive as individuals, there are safeguards for those trees that take more than their share of nutrients. If they do not give back to the ecosystem, genetically they will die out over time (how do scientists work this shit out!?).

Trees also need rest and the continual light provided in some urban settings can deprive trees of sleep causing poor health and even death in some tree species – just like us.

So…what’s this blog all about?

There is much to learn from nature if we are to survive as a species on this planet. We have been on Earth for a mere blink of an eye, but as we have modernised we have made a bloody mess of things – buggering our environment and building companies that have done more harm than good.

This quote, from Ursula Le Guin, sums it up for me:

"To use the world well, to be able to stop wasting it and our time in it, we need to re-learn our being in it."

For Collective Intelligence, 2022 is our fifteenth year in business and it is also the year that we will be activating our people ecosystem. We’ll be using technologies and human connections to mobilise our membership to help each other in our respective spheres of influence.

Already we are seeing our members stepping up with ideas of what they want to be a part of. Here’s some examples:

- Michelle Middleberg and Mary-Beth Robles are working on creating a new team model that will allow former members to connect up again virtually, and possibly locally. Our alumni miss the conversations and culture of the Collective Intelligence teams they once belonged to.

- Finn Shewell, Alana Crooks, and Andy Ayrey are leading a talented team (I call them ‘The Cool Kids’) who are developing a wicked new web platform that our whole ecosystem will be able to connect up on. Our people will be able to access people they can trust easily, on a non-social-media platform. Plus

- Alex Hannant and a few others are currently exploring the new world of Web 3.0, and how that can be integrated into our ecosystem model.

All of the above has been instigated spontaneously in an environment where good ideas hit fertile ground and take root. So, what else can we do?

People are like trees – we are better and stronger when we work together

As an individual, I am really into relearning and reimagining the constraints of how we have always done things, and as a founder I want to let go of any perceived ‘control’ I have more and more.

I dream of Collective Intelligence evolving from being a founder-led ecosystem, to a founder-inspired one. And I am going to turn to nature to learn how to do this.

Will you join me?

Collective Intelligence 2022 ©