Ph: 06 280 0938

Leo Murray: Reflections from the Coal Face of Colonialism

(This blog has been reproduced (with permission!) from an article on Leo’s own website Why Waste )

When I first heard Pania Newton speak about Ihumātao I was riveted. Inspired.

But it wasn’t necessarily the site-specific Ihumātao story, it was the whakaaro her struggle represented. The concept, the thought, the ideology. It was also Pania’s mana.

I was inspired by the way she carried the burden of truth about the world. I was inspired by the way she chose to use her law degree to fight a broken system, despite being so well equipped to profit from it. I was inspired by the way she stood up for what she believed, a rare quality in this culture of apathy. Even closer to home, Pania’s mission embodied an idea that was all too close to my heart.

‘Find a place in the world that you love and care for it’ is Charles Eisenstein’s response to the common narrative around climate change. That narrative that CO2 is this big boogyman, and that all other attempts to create change are futile. Yeah you know the one.

To me, the obsession people have with climate temperature reinforces a reductionist, scientific worldview that nature is this benign ‘thing’ that serves only as an ecological sand pit for elite humans to play games like ‘economy’ and ‘power’. This is the narrative that paved the world in concrete, now crumbling. Through the cracks of the industrial growth paradigm, the shoots of a new (and ancient) story are beginning to show. In this story the world is a living being. Humans are simply and purposefully, a part of that living being.

This wahine toa, this warrior woman’s struggle to defend sacred ancestral land embodied the new story. It encouraged me embrace my struggles and use them to fan the flames of my own burning desire for a new story for humanity.

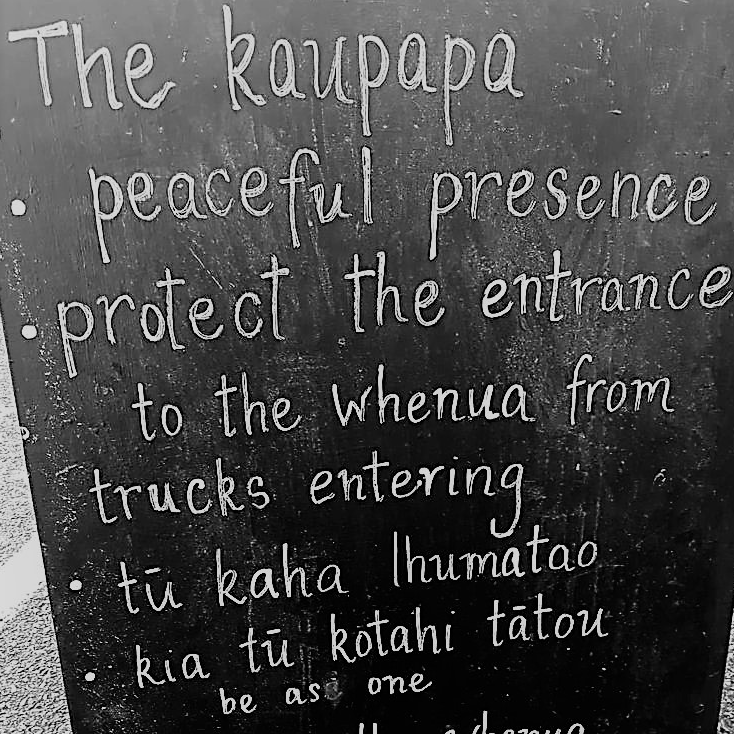

Last week I visited Ihumātao with Ayla. The kaupapa was clear, the on-boarding was tight. The box of veges we bought was received and recorded into a system. The huge kitchen tent was constantly busy. I had some questions, so I asked at info. I got hungry, so I ate some kai. If you wanna learn a thing or two about how to do civil disobedience well – go to Ihumātao and learn it from the tangata whenua.

Setting up the tent in the rain on a foggy paddock, I peered along the frontline. The murky edges of right and wrong. Freedom and imprisonment. The police on one side, the resistance on the other. Middle of winter huddled around fires for days, weeks, months. I got the feeling that everyone there was just playing a game.

What was my role?

When people asked, I replied ‘kotahitanga’. Approving nods. I was there to show solidarity.

But was that really my answer? And was it of any value? Or was I simply being voyeuristic?

What does it mean to be Pākehā at an indigenous land protest? Indeed, what does it mean to be Pākehā in contemporary Aotearoa-New Zealand? Another blog entry perhaps…

What I do know is that colonisation isn’t finished. And my reflections from the coal face of colonialism reminded me of how disruptive the severing of whakapapa can be. I saw through a trans-contextual lens that our addiction to comfort and culture of consumerism is simply a coping mechanism for our lost relationship to the earth.

Gaia. Pachamama. Maya. Papatūānuku.

Yet here I was. Soaking wet, sitting on a piece of cardboard next to the fire, listening to that classic Māori strum – singing songs with a bunch of people who could trace their lineage back to the earth mother itself.

This is true wealth. And in that moment, I realised they weren’t there to reclaim their stolen land. Instead, those Māori-identifying people were in that paddock singing songs to reclaim their stolen culture.

I believe that is worth standing for/with. Kotahitanga.

At what point do we drop our suspicion on whether ‘myths and legends’ are true and accept that our relationship to the planet sucks, and that mātauranga Māori is simply a better working model?

‘Stop buying shit and go be in nature’ was Ayla’s summary. Yup.

Fletchers was rolling out the Kiwi dream. Save Our Unique Landscape a spanner in the works of the GDP consumer machine. Hold up. Do we really need more malls and greenfield sprawls over some of the most fertile lands in the motu? This sure sounds familiar, with stories of produce from Ihumātao feeding hungry settlers during difficult winters.

In my opinion, the conflict at Ihumātao is more about the difference in worldview between people who believe the land belongs to them, and people who believe they belong to the land.

We are all indigenous to somewhere, cut off from our ancestry through colonial imperialism, unable to fulfil our purpose as kaitiakitanga – the guardians and gardeners of this planet.

So, the most pressing question may not be ‘should we prevent Fletchers from building a subdivision on historic, sacred and fertile land?’ but, ‘how do we want to progress as a nation full of people somewhere on a spectrum between these two worldviews?’

With Ihumātao as a present and poignant catalyst for this discussion, my desire is that we take the opportunity as a people to recognise that the Earth was here before us, and will be here long after we have gone – and act with that in mind.

Whatungarongaro te tangata, toitū te whenua

As man disappears from sight, the land remains.

Kia kaha, people of Ihumātao.

Leo Murray – August 2019

Collective Intelligence 2022 ©